What Is a Good P/E Ratio? (By Industry, With Examples)

10/11/2025

What Is a Good P/E Ratio?

In this article, we’ll explain in simple terms what the P/E ratio means, how it’s calculated, and how to judge whether a P/E is “good.” We’ll look at historical benchmarks, compare P/E ratios by industry (for example, tech vs. utilities), and discuss differences between growth stocks and value stocks. We’ll focus on the U.S. stock market (like the S&P 500 and major U.S. companies) with context that applies globally. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of how to use the P/E ratio as a tool in evaluating stocks.

Understanding the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

The P/E ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) tells you how much investors are paying for each dollar of a company’s earnings. In formula form, P/E = Share Price ÷ Earnings Per Share (EPS).

For example, if a company’s stock trades at $120 per share and its EPS (earnings per share) is $5, then its P/E ratio is 24 (meaning the stock is priced at 24 times its earnings). In plain language, a P/E of 24 indicates investors are willing to pay $24 for every $1 of the company’s earnings. A high P/E ratio means the stock price is high relative to earnings. This could signal that investors expect higher growth in the future, or it could mean the stock might be overvalued at the moment. Conversely, a low P/E ratio means the stock price is low compared to earnings. That can indicate a potentially undervalued stock or a company that’s very profitable relative to its price. However, context is critical – a low P/E isn’t automatically “good” and a high P/E isn’t automatically “bad” without further analysis.

How the P/E Ratio is Calculated (Simple Example)

Calculating the P/E ratio is straightforward. Here are the steps:

- Find the Earnings Per Share (EPS): This is the company’s net profit divided by the number of outstanding shares. For instance, if a company earned $10 billion over the last year and has 2 billion shares outstanding, its EPS would be $5 per share (i.e. $10 billion ÷ 2 billion shares).

- Divide the Share Price by EPS: If that company’s current stock price is $120, then P/E = $120 ÷ $5 = 24. In this example, the stock’s P/E ratio is 24. This tells us the stock is trading at 24 times its earnings. Another way to interpret this: investors are paying $24 for each $1 of the company’s earnings.

It’s that simple. You can usually find both price and EPS readily – stock prices are listed on any exchange, and EPS can be found in a company’s financial statements or on finance websites. Note that P/E can be calculated using trailing earnings (past 12 months of actual earnings) or forward earnings (projected earnings for the next year). The concept is the same; the difference is whether you use past EPS or expected future EPS in the calculation. Trailing P/E is based on actual reported earnings, while forward P/E uses analysts’ or management’s earnings forecasts. Beginners should be aware of which one is being quoted, but in either case, the P/E represents a price-to-earnings multiple.

What Is Considered a "Good" P/E Ratio?

When is a P/E ratio “good”? The truth is, there’s no single magic number. A “good” P/E ratio depends on context – the company’s industry, the overall market, and the company’s growth prospects all matter. That said, we can discuss some general benchmarks and guidelines to help you understand the range of P/E ratios.

Historical market averages

Historically, the overall U.S. stock market (for example, the S&P 500 index) has traded at a P/E ratio of around 15–16 on average over the long term. This is often considered a baseline for a “normal” market valuation. If a stock’s P/E is near that long-term market average, you might consider it fairly valued relative to history. If it’s significantly lower, it could be potentially undervalued, and if it’s much higher, it could be overvalued – but remember, this is just a starting point.

Recent norms

In more recent years, P/E ratios have trended higher than the 20th-century historical average. Many investors consider a P/E in the range of roughly 20 to 25 to be a typical average in modern market conditions. In fact, financial analysts often cite that any P/E ratio below about 20-25 could be considered “good” or at least acceptable in terms of not being overpriced. For example, if the market average is around 22, a stock with a P/E of 18 might catch a value investor’s attention as potentially cheap relative to the market. On the other hand, a stock with a P/E of 30+ might be viewed as expensive unless it has high growth to justify it.

It’s important to note that market-wide P/E ratios fluctuate over time. During bull markets, overall P/Es often rise; during recessions, earnings can fall and make P/Es look very high even if stock prices drop. For instance, in the last 20 years the P/E of the S&P 500 has swung from as low as about 13 to over 100 at extreme points. (The extremely high P/E occurred in early 2009 when earnings plunged during the recession, driving the ratio up despite lower stock prices.) This illustrates that a “good” P/E must be interpreted in context – a very high P/E might be temporary or misleading if earnings are temporarily depressed.

Comparing P/E to peers and industry

One of the best ways to judge if a P/E is good is to compare it to other similar companies. A P/E that is low relative to a company’s competitors or industry average can signal a bargain (or perhaps a company in trouble – more on that later), while a P/E much higher than peers can signal high growth expectations or an overvalued stock. In general, a P/E ratio below the market or industry average is often considered favorable (good), assuming the company’s fundamentals are solid. The key is that “good” means lower than what’s normal for that particular comparison group. For example, a P/E of 18 might be good for a tech stock if its peers average 25, but a P/E of 18 could be high for a utility stock if its peers average 12.

In summary, there is no single “good” P/E number that applies to every stock. As a rule of thumb, many value-oriented investors like to see P/E ratios in the teens or lower. Benjamin Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor) often looked for stocks with P/E around 15 or less as potentially undervalued. Today, a P/E under 20 is often considered reasonable, and the sweet spot for many investors might be something like 15–20 for a stable company. But you must adjust your expectations by industry and consider why a stock’s P/E is where it is.

P/E Ratios by Industry: Why They Vary

P/E ratios can vary drastically by industry. What counts as a “good” P/E in one sector could be completely different in another. This is because industries have different typical growth rates, risk profiles, and business models. Here’s a look at how P/Es differ across sectors:

High-Tech and Growth Industries

These tend to have higher P/E ratios on average. Investors in tech, biotech, or internet sectors are often willing to pay a premium for future growth. For example, the technology sector in the U.S. has an average P/E around the mid-20s, and many software or internet companies often trade at 30+ times earnings. In one analysis, technology companies had an industry average P/E of about 26. High-growth tech giants can have even higher multiples. It’s not unusual to see popular tech stocks with P/E ratios well above 30 or 40 when growth expectations are strong.

Energy (Oil & Gas)

Traditional energy companies often have lower P/E ratios. These businesses are cyclical and subject to commodity price swings, so investors tend to pay less for each dollar of earnings. For instance, the oil and gas industry in a recent period had an average P/E of around 6 – extremely low compared to the market. That was partly due to strong earnings when oil prices spiked, making the stocks look cheap on a trailing earnings basis. A P/E in the single digits is common for oil producers, especially when their earnings are at a cyclical high. So, an oil company might look “cheap” with a P/E of 8 – but in that industry, single-digit P/Es are normal and not necessarily a sign of a bargain. (It could even signal peak earnings.)

Financial Services (Banks)

Banks and insurance companies also typically sport low P/E ratios, often in the low teens or single digits. Their growth is modest and tied to interest rates and economic cycles. For example, in early 2025 the diversified banking industry in the U.S. had an average P/E under 8. It’s not uncommon for large banks to trade with P/Es around 10–12 in a normal environment. Thus, a bank stock with a P/E of 8 or 9 might be considered attractive relative to history, whereas a tech stock with that P/E would be extraordinarily low (and possibly a red flag that something is wrong!).

Consumer Staples and Retail

Consumer staples companies (like food, beverage, household product makers) often have moderate P/Es, typically somewhere in the high teens to 20s. These are stable, slow-growing businesses but with steady demand, so investors are willing to pay a bit more for stability. For instance, Coca-Cola, a classic consumer staples stock, has a P/E around 23–24 in 2025, which is in line with the broader market. Retail companies can range widely: a high-growth e-commerce retailer might have a high P/E, while a slow-growth brick-and-mortar retailer might have a low P/E.

Utilities

Utility companies (electric, gas, water utilities) generally have lower P/E ratios. They are regulated, with stable but slow-growing earnings, so historically their P/Es are often in the low-teens or even single digits. For example, many utility stocks often trade with P/E ratios around 10 to 20 depending on the interest rate environment. (When interest rates are low, investors pay more for utilities’ steady dividends, which can raise their P/Es; when rates are high, utilities’ P/Es tend to compress.) In early 2025, some utility industry P/Es were quite low – one data source showed the electric utilities sector with an average P/E in the low teens or single digits. So, a “good” P/E for a utility might be substantially lower than a “good” P/E for a tech company.

Real Estate (REITs)

Real Estate Investment Trusts have varied P/Es and sometimes use a different metric (funds from operations, FFO, instead of earnings). But generally, property REITs might trade in the teens or 20s P/E, whereas certain specialty REITs (like data center REITs) can have very high P/E ratios (the data center REIT industry had an average P/E near 95 in early 2025, due to strong growth prospects and accounting nuances). This is a reminder that extremely high P/Es can occur in niches, and one should dig into the reasons.

These examples demonstrate why you must compare a stock’s P/E to its industry peers. A “good” P/E ratio is relative – what’s low for one sector could be high for another. Analysts often say “compare apples to apples” when evaluating P/E: compare a tech stock’s P/E to other tech stocks, a bank to other banks, etc. A P/E significantly below the industry average might indicate a value opportunity (or possibly company-specific troubles), while a P/E above the industry average could indicate higher growth expectations (or an overvalued stock).

Growth Stocks vs. Value Stocks: P/E Differences

Investors often categorize stocks as “growth” or “value” based in part on their P/E ratios:

Growth Stocks

These are companies expected to grow earnings at an above-average rate. Growth stocks usually have high P/E ratios. Investors are willing to pay more per dollar of current earnings because they expect those earnings to increase rapidly in the future. A high P/E, in this case, signals optimism about future growth. For example, consider Tesla. It’s often viewed as a growth stock in the automotive/tech space. In 2025, Tesla’s P/E ratio was well into the triple digits (over 200) based on trailing earnings – a reflection that investors anticipate far higher future earnings and are pricing the stock accordingly. Even at earlier points, Tesla traded around 40–50 times earnings while traditional automakers were around 10×, illustrating how growth expectations justify a much higher multiple. Other growth stocks might include young tech companies, innovative biotech firms, or any company reinvesting heavily for expansion. Sometimes growth companies have no profits yet (earnings are zero or negative), so they effectively have no P/E or a meaningless P/E (often shown as N/A because earnings are not positive). Investors in these cases focus on future earnings potential. It’s common to see P/E ratios above 30 (or no P/E at all) in high-growth sectors – this isn’t “bad” per se, but it means investors have high expectations. If those expectations falter, high-P/E stocks can see sharp price drops.

Value Stocks

These are companies that are considered undervalued or out-of-favor, often with lower P/E ratios. Value stocks typically are mature businesses with steady or slow growth, or companies that have fallen out of favor due to some challenges but still have solid fundamentals. Investors look at low P/E ratios (relative to the market or industry) as a sign that a stock might be a bargain – essentially “on sale”. As a rough guideline, stocks with P/Es in the single digits are often labeled value stocks. For example, many financial and energy stocks in recent times have had P/Es below 10, fitting the value profile. A company like Exxon Mobil, with a P/E around 15–16 in 2025, could be seen as value-leaning compared to the overall market (since 15 is below the market’s ~20+ average). Classic value stocks often include utilities, telecoms, manufacturers, or any business with stable earnings but limited growth – investors won’t pay high multiples for these, so their P/Es stay low.

It’s important to understand that “low P/E” doesn’t always mean “good investment.” Sometimes a stock has a low P/E for a reason. A company with declining earnings or facing big risks might have a cheap valuation because investors aren’t optimistic about its future. As one investment podcast noted, you shouldn’t automatically mistake a low P/E as meaning a company is undervalued – it may simply reflect lower growth prospects or other issues. For instance, if a company’s industry is in decline, all the peers might also have low P/Es. Conversely, a very high P/E stock isn’t guaranteed to succeed – if the growth doesn’t pan out, the stock can crash. In general, growth stocks = high P/E, value stocks = low P/E. Some analysts use specific cut-offs: companies with P/Es above ~30 are often considered growth stocks, while those with P/Es below ~10 are seen as value stocks. These are not strict rules, but they underscore the contrast. Many investors blend these concepts, seeking a “Growth at a Reasonable Price (GARP)” – meaning they’ll buy growth companies but only if the P/E isn’t exorbitantly high relative to the growth rate. That introduces the idea of the PEG ratio (price/earnings to growth), which is beyond our scope here, but it’s another tool investors use to gauge if a high-P/E growth stock might still be a good value when growth is factored in.

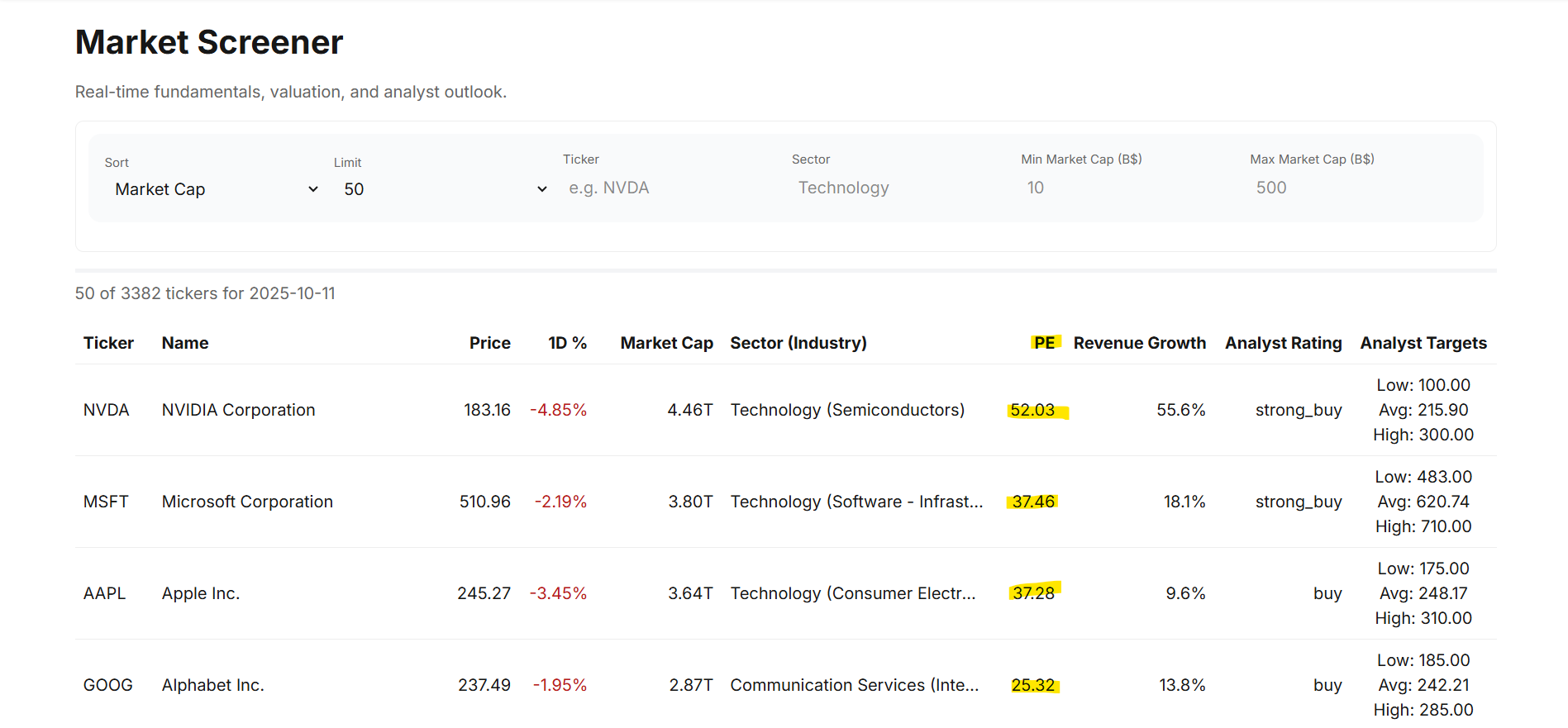

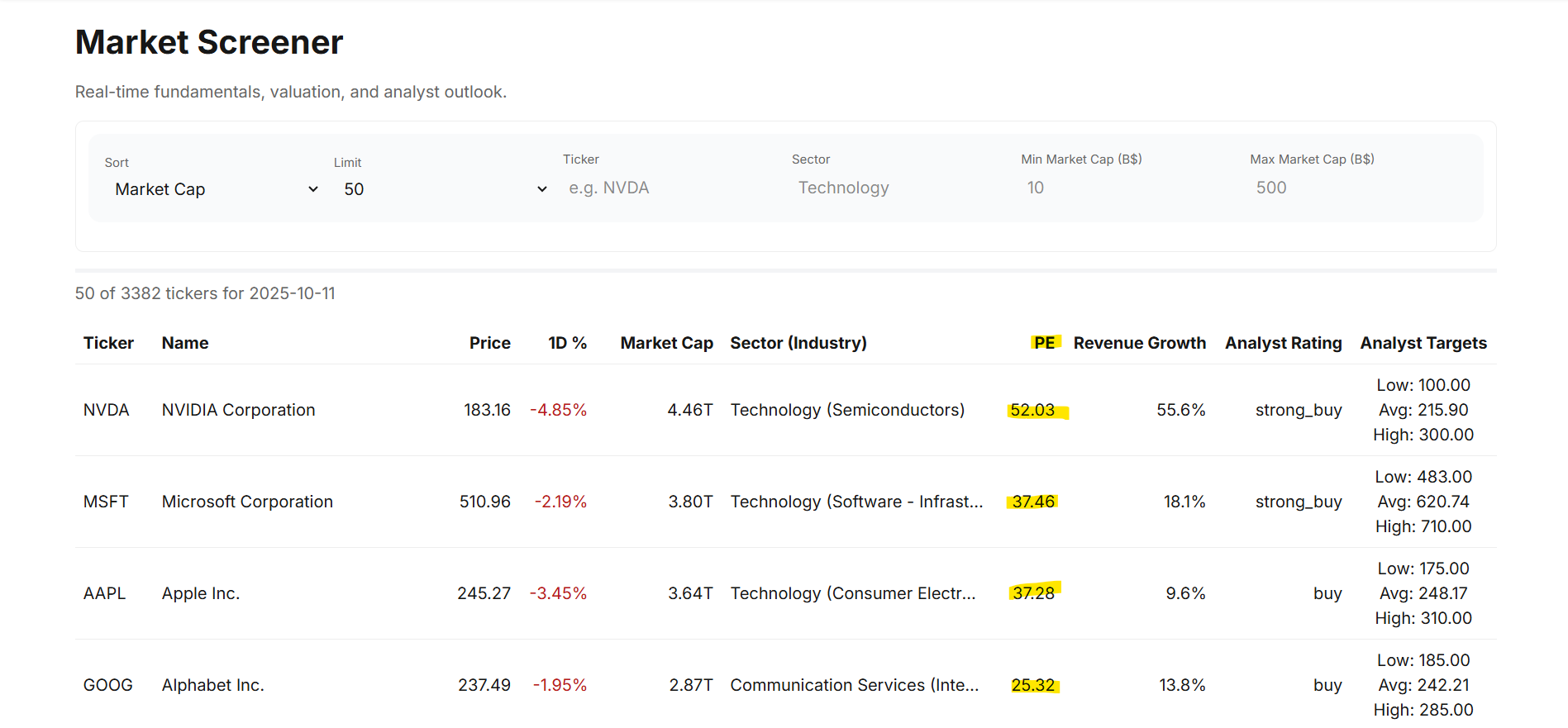

Examples: P/E Ratios of Major Companies

Let’s look at some real-world examples of well-known U.S. companies and their current P/E ratios (as of late 2025). This will illustrate how varied P/E ratios can be and help put the above concepts into perspective:

| Company (Sector) | P/E Ratio (TTM) | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Apple (AAPL) – Tech Hardware | ~37 | Apple is a mega-cap tech company with steady growth. Its P/E in the high-30s suggests investors still see good growth prospects ahead, and it trades at a premium to the market average. This is a fairly typical P/E for a successful technology stock – higher than the overall market, but not extreme for a company with strong earnings and brand dominance. |

| Tesla (TSLA) – Automaker/Tech | ~221 | Tesla’s triple-digit P/E reflects it as a high-growth stock. Investors are paying over 200 times current earnings, indicating they expect massive future earnings growth. Such a P/E is extraordinarily high; it’s justified only by strong belief in Tesla’s expansion (and perhaps optimistic hype). It’s an example of a stock where the P/E is not “good” in the value sense, but can be normal for a hot growth company. |

| Coca-Cola (KO) – Consumer Staples | ~24 | Coca-Cola’s P/E in the low-to-mid 20s is close to the market average. As a stable consumer staples giant, this moderate P/E suggests the stock is fairly valued. Investors are willing to pay about $23–$24 per $1 of Coke’s earnings, reflecting its steady (but not high) growth and reliable profits. This P/E range is common for blue-chip consumer goods companies. |

| Exxon Mobil (XOM) – Energy (Oil & Gas) | ~16 | Exxon’s P/E in the mid-teens is relatively low compared to the overall market, fitting its profile as a value/cyclical stock. Energy companies often carry lower P/Es. A P/E around 16 for Exxon suggests either a cautious outlook by investors or strong earnings (or both). It’s arguably a “good” P/E in that it’s below market average – if you believe in the company’s stability – but in the oil industry context, mid-teens is actually on the higher side (since many oil peers are single-digit). |

TTM = Trailing Twelve Months (based on past 12 months earnings). As you can see, different companies (and sectors) show very different P/E ratios at the same point in time. Tesla’s extremely high P/E embodies a growth stock with lofty expectations, while Exxon’s lower P/E shows a value-tilted stock in a mature industry. Apple and Coca-Cola sit somewhere in between, with P/Es reflecting solid companies with decent (but not explosive) growth. The key takeaway is that a “good” P/E must be interpreted relative to each company’s context. If you compared Tesla’s P/E to Exxon’s directly, you’d conclude Tesla looks wildly overvalued – but relative to Tesla’s growth plans in the tech/EV space, investors see that multiple as (perhaps) justified. Conversely, Exxon’s P/E looks cheap next to Apple’s, but Apple is a tech leader with faster growth than Exxon, so a higher multiple is expected.

Key Takeaways on Using the P/E Ratio

- The P/E ratio is a simple but powerful metric for stock valuation. It tells you how many dollars you’re paying for each dollar of earnings. Use it as a starting point to gauge valuation.

- A “good” P/E ratio is relative. There is no fixed number that is universally good. Compare a stock’s P/E with the market average, its industry peers, and its own historical P/E range to judge its valuation.

- Historical benchmarks: The U.S. market’s long-term average P/E is around 15–16, but in recent years 20+ is common. A P/E lower than the prevailing market average can be considered attractive, if other factors are positive.

- Industry matters: Know the typical P/E range for the sector. Tech and growth industries have higher P/E ratios, while sectors like utilities, energy, and finance have lower P/Es. Always compare like with like.

- Growth vs. value: High P/E stocks (growth stocks) can be good investments if the company delivers growth, but they carry more risk if expectations aren’t met. Low P/E stocks (value stocks) might be undervalued opportunities or could be cheap for a reason. A balanced view considers the company’s growth prospects alongside the P/E.

- Global context: The concept of P/E applies globally – whether you’re looking at U.S., European, or Asian stocks, P/E is a common metric. However, average P/Es can vary by country or region based on economic conditions and market compositions. Always consider local market norms when evaluating international stocks.

- Consider other factors: Don’t use P/E in isolation. It’s a quick check, not the final word. A stock with a “good” P/E might have other issues (high debt, declining industry) that make it a bad investment. Likewise, a high P/E stock might have unique strengths that justify the valuation. It’s wise to also look at other metrics like PEG ratio, P/B (price-to-book), P/S (price-to-sales), dividend yield, and of course the company’s growth rates and fundamentals. If a company has no earnings or negative earnings, the P/E ratio isn’t applicable (it will be listed as N/A) – in such cases, other metrics must be used.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the P/E ratio is a useful tool for beginners and experienced investors alike to assess stock valuation. A “good” P/E ratio generally means you’re not overpaying for a stock’s earnings relative to some benchmark. For a beginner, a practical approach is: look for companies with P/E ratios not too far above the market or industry average, unless you have strong reason to believe their growth will outperform. And if you find a stock with a much lower P/E than its peers, investigate why – it could be an undervalued gem or a value trap. By understanding the P/E ratio in context, you can make more informed decisions and blend this insight with other analysis to build a solid investment strategy. Happy investing!

Ready to apply this? Use the Finance Halo P/E Stock Screener to filter stocks by trailing or forward P/E, sector, market cap, dividend yield, and more.

What Is a Good P/E Ratio?

Understanding if a stock’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is “good” is a common question for beginner investors. The P/E ratio is one of the most widely used stock valuation metrics, but what qualifies as a good P/E ratio can vary.

What Is a Good P/E Ratio?

In this article, we’ll explain in simple terms what the P/E ratio means, how it’s calculated, and how to judge whether a P/E is “good.” We’ll look at historical benchmarks, compare P/E ratios by industry (for example, tech vs. utilities), and discuss differences between growth stocks and value stocks. We’ll focus on the U.S. stock market (like the S&P 500 and major U.S. companies) with context that applies globally. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of how to use the P/E ratio as a tool in evaluating stocks.

Understanding the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

The P/E ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) tells you how much investors are paying for each dollar of a company’s earnings. In formula form, P/E = Share Price ÷ Earnings Per Share (EPS).

For example, if a company’s stock trades at $120 per share and its EPS (earnings per share) is $5, then its P/E ratio is 24 (meaning the stock is priced at 24 times its earnings). In plain language, a P/E of 24 indicates investors are willing to pay $24 for every $1 of the company’s earnings. A high P/E ratio means the stock price is high relative to earnings. This could signal that investors expect higher growth in the future, or it could mean the stock might be overvalued at the moment. Conversely, a low P/E ratio means the stock price is low compared to earnings. That can indicate a potentially undervalued stock or a company that’s very profitable relative to its price. However, context is critical – a low P/E isn’t automatically “good” and a high P/E isn’t automatically “bad” without further analysis.

How the P/E Ratio is Calculated (Simple Example)

Calculating the P/E ratio is straightforward. Here are the steps:

- Find the Earnings Per Share (EPS): This is the company’s net profit divided by the number of outstanding shares. For instance, if a company earned $10 billion over the last year and has 2 billion shares outstanding, its EPS would be $5 per share (i.e. $10 billion ÷ 2 billion shares).

- Divide the Share Price by EPS: If that company’s current stock price is $120, then P/E = $120 ÷ $5 = 24. In this example, the stock’s P/E ratio is 24. This tells us the stock is trading at 24 times its earnings. Another way to interpret this: investors are paying $24 for each $1 of the company’s earnings.

It’s that simple. You can usually find both price and EPS readily – stock prices are listed on any exchange, and EPS can be found in a company’s financial statements or on finance websites. Note that P/E can be calculated using trailing earnings (past 12 months of actual earnings) or forward earnings (projected earnings for the next year). The concept is the same; the difference is whether you use past EPS or expected future EPS in the calculation. Trailing P/E is based on actual reported earnings, while forward P/E uses analysts’ or management’s earnings forecasts. Beginners should be aware of which one is being quoted, but in either case, the P/E represents a price-to-earnings multiple.

What Is Considered a "Good" P/E Ratio?

When is a P/E ratio “good”? The truth is, there’s no single magic number. A “good” P/E ratio depends on context – the company’s industry, the overall market, and the company’s growth prospects all matter. That said, we can discuss some general benchmarks and guidelines to help you understand the range of P/E ratios.

Historical market averages

Historically, the overall U.S. stock market (for example, the S&P 500 index) has traded at a P/E ratio of around 15–16 on average over the long term. This is often considered a baseline for a “normal” market valuation. If a stock’s P/E is near that long-term market average, you might consider it fairly valued relative to history. If it’s significantly lower, it could be potentially undervalued, and if it’s much higher, it could be overvalued – but remember, this is just a starting point.

Recent norms

In more recent years, P/E ratios have trended higher than the 20th-century historical average. Many investors consider a P/E in the range of roughly 20 to 25 to be a typical average in modern market conditions. In fact, financial analysts often cite that any P/E ratio below about 20-25 could be considered “good” or at least acceptable in terms of not being overpriced. For example, if the market average is around 22, a stock with a P/E of 18 might catch a value investor’s attention as potentially cheap relative to the market. On the other hand, a stock with a P/E of 30+ might be viewed as expensive unless it has high growth to justify it.

It’s important to note that market-wide P/E ratios fluctuate over time. During bull markets, overall P/Es often rise; during recessions, earnings can fall and make P/Es look very high even if stock prices drop. For instance, in the last 20 years the P/E of the S&P 500 has swung from as low as about 13 to over 100 at extreme points. (The extremely high P/E occurred in early 2009 when earnings plunged during the recession, driving the ratio up despite lower stock prices.) This illustrates that a “good” P/E must be interpreted in context – a very high P/E might be temporary or misleading if earnings are temporarily depressed.

Comparing P/E to peers and industry

One of the best ways to judge if a P/E is good is to compare it to other similar companies. A P/E that is low relative to a company’s competitors or industry average can signal a bargain (or perhaps a company in trouble – more on that later), while a P/E much higher than peers can signal high growth expectations or an overvalued stock. In general, a P/E ratio below the market or industry average is often considered favorable (good), assuming the company’s fundamentals are solid. The key is that “good” means lower than what’s normal for that particular comparison group. For example, a P/E of 18 might be good for a tech stock if its peers average 25, but a P/E of 18 could be high for a utility stock if its peers average 12.

In summary, there is no single “good” P/E number that applies to every stock. As a rule of thumb, many value-oriented investors like to see P/E ratios in the teens or lower. Benjamin Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor) often looked for stocks with P/E around 15 or less as potentially undervalued. Today, a P/E under 20 is often considered reasonable, and the sweet spot for many investors might be something like 15–20 for a stable company. But you must adjust your expectations by industry and consider why a stock’s P/E is where it is.

P/E Ratios by Industry: Why They Vary

P/E ratios can vary drastically by industry. What counts as a “good” P/E in one sector could be completely different in another. This is because industries have different typical growth rates, risk profiles, and business models. Here’s a look at how P/Es differ across sectors:

High-Tech and Growth Industries

These tend to have higher P/E ratios on average. Investors in tech, biotech, or internet sectors are often willing to pay a premium for future growth. For example, the technology sector in the U.S. has an average P/E around the mid-20s, and many software or internet companies often trade at 30+ times earnings. In one analysis, technology companies had an industry average P/E of about 26. High-growth tech giants can have even higher multiples. It’s not unusual to see popular tech stocks with P/E ratios well above 30 or 40 when growth expectations are strong.

Energy (Oil & Gas)

Traditional energy companies often have lower P/E ratios. These businesses are cyclical and subject to commodity price swings, so investors tend to pay less for each dollar of earnings. For instance, the oil and gas industry in a recent period had an average P/E of around 6 – extremely low compared to the market. That was partly due to strong earnings when oil prices spiked, making the stocks look cheap on a trailing earnings basis. A P/E in the single digits is common for oil producers, especially when their earnings are at a cyclical high. So, an oil company might look “cheap” with a P/E of 8 – but in that industry, single-digit P/Es are normal and not necessarily a sign of a bargain. (It could even signal peak earnings.)

Financial Services (Banks)

Banks and insurance companies also typically sport low P/E ratios, often in the low teens or single digits. Their growth is modest and tied to interest rates and economic cycles. For example, in early 2025 the diversified banking industry in the U.S. had an average P/E under 8. It’s not uncommon for large banks to trade with P/Es around 10–12 in a normal environment. Thus, a bank stock with a P/E of 8 or 9 might be considered attractive relative to history, whereas a tech stock with that P/E would be extraordinarily low (and possibly a red flag that something is wrong!).

Consumer Staples and Retail

Consumer staples companies (like food, beverage, household product makers) often have moderate P/Es, typically somewhere in the high teens to 20s. These are stable, slow-growing businesses but with steady demand, so investors are willing to pay a bit more for stability. For instance, Coca-Cola, a classic consumer staples stock, has a P/E around 23–24 in 2025, which is in line with the broader market. Retail companies can range widely: a high-growth e-commerce retailer might have a high P/E, while a slow-growth brick-and-mortar retailer might have a low P/E.

Utilities

Utility companies (electric, gas, water utilities) generally have lower P/E ratios. They are regulated, with stable but slow-growing earnings, so historically their P/Es are often in the low-teens or even single digits. For example, many utility stocks often trade with P/E ratios around 10 to 20 depending on the interest rate environment. (When interest rates are low, investors pay more for utilities’ steady dividends, which can raise their P/Es; when rates are high, utilities’ P/Es tend to compress.) In early 2025, some utility industry P/Es were quite low – one data source showed the electric utilities sector with an average P/E in the low teens or single digits. So, a “good” P/E for a utility might be substantially lower than a “good” P/E for a tech company.

Real Estate (REITs)

Real Estate Investment Trusts have varied P/Es and sometimes use a different metric (funds from operations, FFO, instead of earnings). But generally, property REITs might trade in the teens or 20s P/E, whereas certain specialty REITs (like data center REITs) can have very high P/E ratios (the data center REIT industry had an average P/E near 95 in early 2025, due to strong growth prospects and accounting nuances). This is a reminder that extremely high P/Es can occur in niches, and one should dig into the reasons.

These examples demonstrate why you must compare a stock’s P/E to its industry peers. A “good” P/E ratio is relative – what’s low for one sector could be high for another. Analysts often say “compare apples to apples” when evaluating P/E: compare a tech stock’s P/E to other tech stocks, a bank to other banks, etc. A P/E significantly below the industry average might indicate a value opportunity (or possibly company-specific troubles), while a P/E above the industry average could indicate higher growth expectations (or an overvalued stock).

Growth Stocks vs. Value Stocks: P/E Differences

Investors often categorize stocks as “growth” or “value” based in part on their P/E ratios:

Growth Stocks

These are companies expected to grow earnings at an above-average rate. Growth stocks usually have high P/E ratios. Investors are willing to pay more per dollar of current earnings because they expect those earnings to increase rapidly in the future. A high P/E, in this case, signals optimism about future growth. For example, consider Tesla. It’s often viewed as a growth stock in the automotive/tech space. In 2025, Tesla’s P/E ratio was well into the triple digits (over 200) based on trailing earnings – a reflection that investors anticipate far higher future earnings and are pricing the stock accordingly. Even at earlier points, Tesla traded around 40–50 times earnings while traditional automakers were around 10×, illustrating how growth expectations justify a much higher multiple. Other growth stocks might include young tech companies, innovative biotech firms, or any company reinvesting heavily for expansion. Sometimes growth companies have no profits yet (earnings are zero or negative), so they effectively have no P/E or a meaningless P/E (often shown as N/A because earnings are not positive). Investors in these cases focus on future earnings potential. It’s common to see P/E ratios above 30 (or no P/E at all) in high-growth sectors – this isn’t “bad” per se, but it means investors have high expectations. If those expectations falter, high-P/E stocks can see sharp price drops.

Value Stocks

These are companies that are considered undervalued or out-of-favor, often with lower P/E ratios. Value stocks typically are mature businesses with steady or slow growth, or companies that have fallen out of favor due to some challenges but still have solid fundamentals. Investors look at low P/E ratios (relative to the market or industry) as a sign that a stock might be a bargain – essentially “on sale”. As a rough guideline, stocks with P/Es in the single digits are often labeled value stocks. For example, many financial and energy stocks in recent times have had P/Es below 10, fitting the value profile. A company like Exxon Mobil, with a P/E around 15–16 in 2025, could be seen as value-leaning compared to the overall market (since 15 is below the market’s ~20+ average). Classic value stocks often include utilities, telecoms, manufacturers, or any business with stable earnings but limited growth – investors won’t pay high multiples for these, so their P/Es stay low.

It’s important to understand that “low P/E” doesn’t always mean “good investment.” Sometimes a stock has a low P/E for a reason. A company with declining earnings or facing big risks might have a cheap valuation because investors aren’t optimistic about its future. As one investment podcast noted, you shouldn’t automatically mistake a low P/E as meaning a company is undervalued – it may simply reflect lower growth prospects or other issues. For instance, if a company’s industry is in decline, all the peers might also have low P/Es. Conversely, a very high P/E stock isn’t guaranteed to succeed – if the growth doesn’t pan out, the stock can crash. In general, growth stocks = high P/E, value stocks = low P/E. Some analysts use specific cut-offs: companies with P/Es above ~30 are often considered growth stocks, while those with P/Es below ~10 are seen as value stocks. These are not strict rules, but they underscore the contrast. Many investors blend these concepts, seeking a “Growth at a Reasonable Price (GARP)” – meaning they’ll buy growth companies but only if the P/E isn’t exorbitantly high relative to the growth rate. That introduces the idea of the PEG ratio (price/earnings to growth), which is beyond our scope here, but it’s another tool investors use to gauge if a high-P/E growth stock might still be a good value when growth is factored in.

Examples: P/E Ratios of Major Companies

Let’s look at some real-world examples of well-known U.S. companies and their current P/E ratios (as of late 2025). This will illustrate how varied P/E ratios can be and help put the above concepts into perspective:

| Company (Sector) | P/E Ratio (TTM) | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Apple (AAPL) – Tech Hardware | ~37 | Apple is a mega-cap tech company with steady growth. Its P/E in the high-30s suggests investors still see good growth prospects ahead, and it trades at a premium to the market average. This is a fairly typical P/E for a successful technology stock – higher than the overall market, but not extreme for a company with strong earnings and brand dominance. |

| Tesla (TSLA) – Automaker/Tech | ~221 | Tesla’s triple-digit P/E reflects it as a high-growth stock. Investors are paying over 200 times current earnings, indicating they expect massive future earnings growth. Such a P/E is extraordinarily high; it’s justified only by strong belief in Tesla’s expansion (and perhaps optimistic hype). It’s an example of a stock where the P/E is not “good” in the value sense, but can be normal for a hot growth company. |

| Coca-Cola (KO) – Consumer Staples | ~24 | Coca-Cola’s P/E in the low-to-mid 20s is close to the market average. As a stable consumer staples giant, this moderate P/E suggests the stock is fairly valued. Investors are willing to pay about $23–$24 per $1 of Coke’s earnings, reflecting its steady (but not high) growth and reliable profits. This P/E range is common for blue-chip consumer goods companies. |

| Exxon Mobil (XOM) – Energy (Oil & Gas) | ~16 | Exxon’s P/E in the mid-teens is relatively low compared to the overall market, fitting its profile as a value/cyclical stock. Energy companies often carry lower P/Es. A P/E around 16 for Exxon suggests either a cautious outlook by investors or strong earnings (or both). It’s arguably a “good” P/E in that it’s below market average – if you believe in the company’s stability – but in the oil industry context, mid-teens is actually on the higher side (since many oil peers are single-digit). |

TTM = Trailing Twelve Months (based on past 12 months earnings). As you can see, different companies (and sectors) show very different P/E ratios at the same point in time. Tesla’s extremely high P/E embodies a growth stock with lofty expectations, while Exxon’s lower P/E shows a value-tilted stock in a mature industry. Apple and Coca-Cola sit somewhere in between, with P/Es reflecting solid companies with decent (but not explosive) growth. The key takeaway is that a “good” P/E must be interpreted relative to each company’s context. If you compared Tesla’s P/E to Exxon’s directly, you’d conclude Tesla looks wildly overvalued – but relative to Tesla’s growth plans in the tech/EV space, investors see that multiple as (perhaps) justified. Conversely, Exxon’s P/E looks cheap next to Apple’s, but Apple is a tech leader with faster growth than Exxon, so a higher multiple is expected.

Key Takeaways on Using the P/E Ratio

- The P/E ratio is a simple but powerful metric for stock valuation. It tells you how many dollars you’re paying for each dollar of earnings. Use it as a starting point to gauge valuation.

- A “good” P/E ratio is relative. There is no fixed number that is universally good. Compare a stock’s P/E with the market average, its industry peers, and its own historical P/E range to judge its valuation.

- Historical benchmarks: The U.S. market’s long-term average P/E is around 15–16, but in recent years 20+ is common. A P/E lower than the prevailing market average can be considered attractive, if other factors are positive.

- Industry matters: Know the typical P/E range for the sector. Tech and growth industries have higher P/E ratios, while sectors like utilities, energy, and finance have lower P/Es. Always compare like with like.

- Growth vs. value: High P/E stocks (growth stocks) can be good investments if the company delivers growth, but they carry more risk if expectations aren’t met. Low P/E stocks (value stocks) might be undervalued opportunities or could be cheap for a reason. A balanced view considers the company’s growth prospects alongside the P/E.

- Global context: The concept of P/E applies globally – whether you’re looking at U.S., European, or Asian stocks, P/E is a common metric. However, average P/Es can vary by country or region based on economic conditions and market compositions. Always consider local market norms when evaluating international stocks.

- Consider other factors: Don’t use P/E in isolation. It’s a quick check, not the final word. A stock with a “good” P/E might have other issues (high debt, declining industry) that make it a bad investment. Likewise, a high P/E stock might have unique strengths that justify the valuation. It’s wise to also look at other metrics like PEG ratio, P/B (price-to-book), P/S (price-to-sales), dividend yield, and of course the company’s growth rates and fundamentals. If a company has no earnings or negative earnings, the P/E ratio isn’t applicable (it will be listed as N/A) – in such cases, other metrics must be used.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the P/E ratio is a useful tool for beginners and experienced investors alike to assess stock valuation. A “good” P/E ratio generally means you’re not overpaying for a stock’s earnings relative to some benchmark. For a beginner, a practical approach is: look for companies with P/E ratios not too far above the market or industry average, unless you have strong reason to believe their growth will outperform. And if you find a stock with a much lower P/E than its peers, investigate why – it could be an undervalued gem or a value trap. By understanding the P/E ratio in context, you can make more informed decisions and blend this insight with other analysis to build a solid investment strategy. Happy investing!

Ready to apply this? Use the Finance Halo P/E Stock Screener to filter stocks by trailing or forward P/E, sector, market cap, dividend yield, and more.